Arctic Monkeys: Get Off The Bandwagon, Put Down The Handbook

The story behind Arctic Monkeys’ debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, which propelled four lads - fresh from high school - to the top of the UK music scene. Released just two-and-a-half years after the band’s first gig, the album became the fastest selling debut in British music history.

26th August 2006. The end-of-summer bank holiday is in full swing and the sun has set on the Saturday night of the iconic Reading Festival. A sense of anticipation fills the air as the largest crowd of the weekend gathers in front of the festival’s main stage. Scheduled to perform between Mike Skinner’s The Streets and headliners Muse is a band surrounded by the most intense hype and hysteria since Beatlemania in the 60s; a band who released the fastest-selling debut album in British music history seven months prior; a band who played their first gig only three years earlier.

The sleazy saxophone hook of ‘Taken’ by Francis Monkman – from the soundtrack of the 80s London gangster film The Long Good Friday – plays from the stage’s PA system, and four semi-scruffy 20-year-old lads from Sheffield saunter onstage. In trademark fashion, the band’s entrance comes without fanfare or fuss; no stylish backdrop or elaborate stage production, no on-mic introduction or hello. The stage remains in near-darkness; the silhouettes on stage barely visible. The crowd’s reaction is understated; they wait for a signal to lose their minds. Four drumstick clicks count in the scratchy opening of the band’s all-conquering debut single, ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’, and the audible screams confirm that the crowd have taken their cue.

Nonchalantly smashing out your first number one single – the song that made you a household name – as the opener of your biggest gig to date would normally be considered an audacious step for a band; something a manager would warn them about doing, concerned that they might encourage a mass exodus from the crowd once the festivalgoers had heard the song that sparked their interest in the band. Arctic Monkeys are a different story, having never opted to follow the textbook approach taken by so many up-and coming indie bands. They weren’t going to start now.

Tens of thousands of Reading punters quickly find their voice. They mimic the now-iconic ascending guitar line from the ‘…Dancefloor’ intro and bellow the start of the song’s final chorus so loud that singer Alex Turner doesn’t even bother joining in. After finishing their opener to the adulation of the audience, droning guitar feedback filling the air, the band quickly rip through the first verse and chorus of ‘Still Take You Home’ before Turner finally acknowledges the crowd’s existence.

‘Well, good evening’.

Almost eight years to the day before their appearance on the Reading Festival main stage, another entrance to a different kind of unfamiliar environment planted the seed for Arctic Monkeys’ (brace for cliché) meteoric rise to the top of British music.

It’s the first day back after the 1998 summer holidays at Stocksbridge High School. Andy Nicholson, age 12, faces the daunting reality of walking into his Year 8 classroom as the new lad at school, having moved to the area from another part of Sheffield. For those unfamiliar with the English school system, Year 8 is the equivalent to your second year in high school, meaning Mr Nicholson was walking into a class of about 30 pupils who had spent the last year becoming friends. To make matters worse, he’s a Blade who’s now surrounded by a flock of Owls; Stocksbridge is predominantly home to Sheffield Wednesday (the Owls) fans – Nicholson is a lifelong supporter of their city rivals, Sheffield United (the Blades).

The first two faces Nicholson spots amongst his new classmates are Alex Turner and Matt Helders, who have been friends since primary school. The pair welcome Nicholson into their group, and the trio spend their lunchtimes playing basketball in the school gym hall. Certainly an understated and innocent beginning for a band that would go on to unite the indie kids and the football lads; forcing people up and down the country to belt out their songs in their best faux-Sheffield accent.

As Turner, Helders, and Nicholson progressed through their teens, their interest in music grew stronger, possibly even reaching the milestone of rivalling sport as the lads’ number one interest. Initially, it was a bond forged from their mutual love for hip-hop (or ‘ip-‘op); Dr Dre, Eminem, Leeds-based Braintax and an obsession with Roots Manuva. Turner would mess about with basic music production software that his dad – a music teacher – had installed on his computer, making hip-hop beats, and Helders had a set of decks to mix vinyl records.

By the time they reached 15 and 16 in the early 2000s, rock – or more generally guitar music – joined hip-hop and rap on the list of genres the trio listened to. This was the time of MTV2 and Kerrang, two music channels that played a more rock-centric alternative to the mainstream pop found on other channels. Guitars would be the common denominator, but the variety of music under this banner would go on to provide a generation of kids with an extensive education of everything from Britpop, heavy American rock/grunge, pop-punk, indie, and even the iconic nu-metal. Those who grew up in front of MTV2 and Kerrang will be familiar with the channel-hopping between the two, the encyclopaedic knowledge of the first few seconds of each music video on each channel’s rotation, the thrill of seeing a run of videos that you particularly like and avoiding some of the stinkers of the time, the fact that these channels even had different ‘programmes’ which would have a slightly different rotation of songs. Sometimes you would even treat yourself to a bit of VH1. It was this act of channel-hopping that would introduce the future Monkeys to the first set of bands that would influence their future output; the likes of The Vines, The Hives, Queens of the Stone Age, and The White Stripes joining the omnipotent Oasis as the primary guitar-based influences on Turner, Helders and Nicholson.

If these bands were the foundation, The Strokes were the spark that really ignited the future direction of the still-to-be-conceived Arctic Monkeys; the spikey riffs, the occasional use of a jazz chord, the club-tinged rhythms that underpinned their songs, and the gang-like attitude towards outsiders. The Monkeys eventually took the best of the biggest musical phenomenon from across the pond since Nirvana and flipped it on its head in their own unique way. After all, they’re not from New York City, they’re from… Sheffield.

But wait, hang on; let’s not get carried away. Here we are talking about The Strokes and their influence on the Arctic Monkeys, when our story still hasn’t even covered the formation of the band.

We didn’t realise before then that it’s something you can do – we just thought that bands were on TV – it didn’t seem like something that people who lived near us did

- Matt Helders

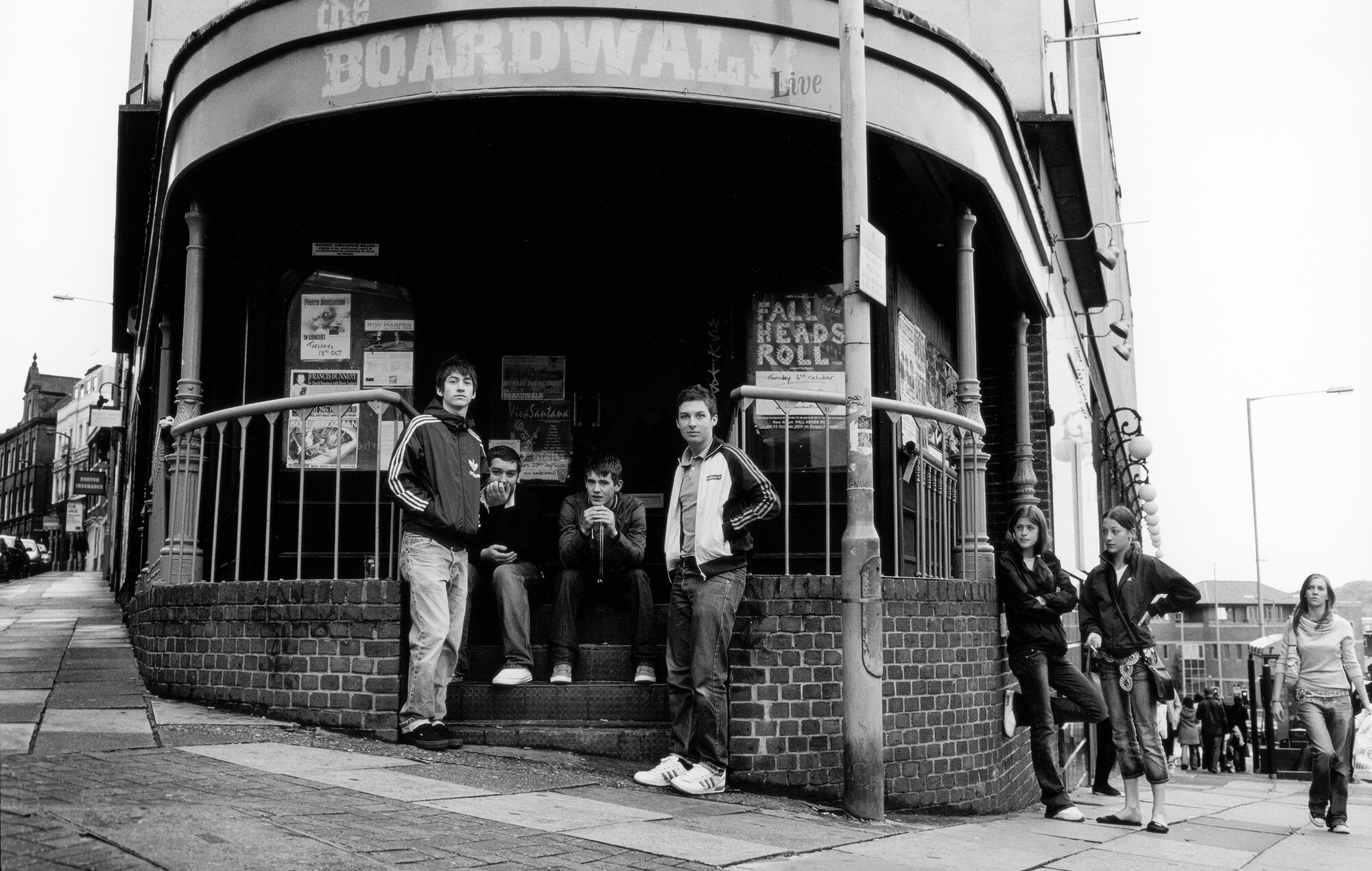

The trio left Stocksbridge High School aged 16 to attend Barnsley College, with Matt Helders poetically describing his motivation for pursuing further education: ‘I only went because everyone else did’. Given their lack of commitment to their continued education, the lads had time to explore other things, getting their first taste of Sheffield nightlife. Some of their friends had formed a band – Milburn – and were playing a gig at the Boardwalk, a local club and music venue that Turner and Nicholson would occasionally work in. The performance from Milburn – led by brothers Joe and Louis Carnall, who are cousins of Arctic Monkeys’ second bassist Nick O’Malley – inspired Turner, Helders, and Nicholson; not because they heard great, life-changing music that night, but because it showed them that being in a band was a realistic possibility, something that they could achieve, something local.

Milburn planted the seed, and the trio set about making their dream – of playing a few covers ‘all the way through without stopping’ – a reality. An emergency meeting was called in Alex Turner’s parent’s home; an induction ceremony, where roles would be assigned. Turner had a grasp of the basics of guitar from his dad’s music teacher influence and had received a guitar the previous Christmas, at the end of 2001. Sorted. Nicholson volunteered to get a guitar of his own, but Turner’s dad suggested that he flipped that idea on its side and cello – he got a bass. With guitar and bass already taken, Matt Helders was left scrambling for his role: ‘it was very inconvenient for me to buy drums because we didn’t have anywhere to put them in our house, but it was the only choice’. He used money from his grandparents to buy a drum kit, and kept it in Turner’s parent’s garage, where the trio started to practice a selection of cover songs.

Unsatisfied with their initial output, Turner suggested drafting in another guitar player to beef up their sound and proposed their neighbour, Jamie Cook. Cook – from a different high school and a year older than the rest of the band – could ‘already play a bit’ and shared the others’ fondness for The Strokes. He even contributed the band name, though the thought process behind the name – which the band themselves have since called rubbish – has never been revealed. One theory is that Cook derived the name from a quote from character Barry the Baptist in Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels gangster caper, where he curses those from northern England as ‘fuckin’ northern monkeys’. Maybe Cook did swap ‘northern’ for ‘arctic’ to arrive at the famously bad band name? The theory remains unconfirmed.

With that, the original Arctic Monkeys line-up was (almost) complete: Alex Turner (‘Al’) and Jamie Cook (‘Cooky’), guitars; Andy Nicholson (‘Andy’ – won’t be remembered as a classic nickname); and Matt Helders (‘Helders’ – dropping the H is optional), drums.

The newly christened Arctic Monkeys returned to the Turner family garage. Was it a case of instant musical chemistry? Did songs perfectly capturing the lives of young, working class Brits in the mid-2000s immediately pour from their brains?

Not quite – their catalogue consisted of covers of The Strokes and The White Stripes, and they didn’t even have a singer. According to Helders, they ‘were just playing and no-one was singing’. Step up Glyn Jones, another friend of the band; the fabled fifth Monkey. Did your excitement peak? Did your heartrate increase? No?

As we already know, Glyn didn’t last long. According to Alex, ‘he was never really into it and we had to force him’. Glyn’s departure meant that Al, the shy guitarist, needed to step up. Turner’s position was simple; he would sing - reluctantly - until they found someone else. 20 years on and they are still waiting; it’s probably for the best.

The band spent an entire year working towards their first gig, determined to be proficient enough to avoid embarrassment and get through their set without a hitch. The stage was set: an early-summer Friday night; 13th June, 2003. The Arctic Monkeys arrive early at The Grapes pub in Sheffield city centre, entering through the front door of the old-school boozer and standing in its homely hall. Through the door on their left is the main bar area, with a few regulars nursing an early evening pint. To their right, the sound of pool balls colliding draws their attention to a couple of younger lads leaning over the red-felt pool table. The band continues through the pub and up the stairs at the opposite end of the hallway, leading to The Grapes’ live music venue.

The Sound, another local band with an even worse name than Arctic Monkeys, are the headline act, and already in the venue. When it’s time for Arctic Monkeys’ sound check, they ask The Sound to leave the room so that they can concentrate on getting the sound right. The Sound left so that the Arctic Monkeys could focus on the sound. The Sound/the sound. Nice.

The Monkeys’ early attention to detail – starting from their first gig – is notable, as most new bands want to rush through sound check and get back to the bar for a few pre-gig pints. Although the band’s early days are often remembered for their famous laidback approach and effortlessness, the year of incessant rehearsal and focus on their first gig’s audio quality shows how serious and focused the band were from day one. Not that crystal-clear audio quality was the only objective of that night at The Grapes; Turner told The Telegraph years later that his aim was ‘just to get to the end of the night and pull the bird that I fancied that I’d got to come down!’

An audience of ‘biased friends and family’ (and the bird Alex fancied) were treated to eight songs. Four covers, showcasing some of the band’s influences – ‘Hotel Yorba’ by the White Stripes, ‘Teenage Kicks’ by The Undertones, ‘Harmonic Generator’ by The Datsuns, and ‘I’m Only Sleeping’ by The Beatles – and four originals; including ‘Ravey Ravey Ravey Club’ and ‘Curtains Closed’. An excerpt from this first gig was uploaded to YouTube and, although slightly-shambolic and more American-accented, the original songs are not far from the sound of the initial demos that sparked major interest in the band.

So was that the beginning of Arctic Monkeys’ meteoric rise to stardom? Were record label executives queued up outside The Grapes with piles of money and recording contracts for the band? Was Jarvis Cocker on hand with a sceptre to officially knight Alex Turner as Sheffield’s new chief wordsmith?

Not exactly – according to Helders, ‘there were a lot less people at our shows 6 months later’.

While not immediately on an obvious trajectory towards success, the band knuckled down to develop their original material and live shows. Key to this was a rehearsal space. Having originally used a disused area of a factory where Matt Helders’ dad worked, the band moved to a rehearsal room in Yellow Arch studios, which they nicknamed Uncle Rodney’s, located in the Neepsend area of Sheffield. Uncle Rodney’s became their base to kick about, practice, play pool, and host impromptu gigs for their friends. In the band’s first NME feature, you can see an England flag with the band name emblazoned across the front, perfectly encapsulating the essence of Uncle Rodney’s; a safe-house, their gang’s hangout.

As more material developed during regular rehearsals, the Arctic Monkeys would cobble together enough money to pay for studio time to record their new songs. Local producer Alan Smyth – who had worked with notable Sheffield acts Pulp and Richard Hawley – would charge unsigned bands £200 for a one-day recording session at his studio, 2fly. This setup allowed Turner and co to quickly build up a collection of demos and they settled into a rhythm, visiting 2fly every few months. According to Alex, the sessions at 2fly were a smooth process; ‘we saved 50 quid each for a full day of recording – 3 songs, got the parts finished by the evening and went for tea while Smyth mixed them there and then. It were all pretty fast’.

Manager Geoff Barradale came on board after the band’s third gig, and immediately started to schedule shows across the North of England. With an ever-increasing collection of demos from their 2fly sessions, the Monkeys got into the habit of spending the night before a gig burning the demos on to discs. They would then hand these out to anyone willing to accept them at their shows. The majority of songs on the band’s record-breaking debut album would begin life as some of these demos – a sign of the quality of their output at such an early stage. As a result, word started to spread about this band of scrappy teenagers from Sheffield; the next big thing.

This was the era of file sharing – where programmes like Limewire and Kazaa would allow people to quickly share MP3 files (dial-up connection dependent) – and Myspace; a perfect environment for the young gig-goers and students, who had witnessed these first Arctic Monkeys shows and picked up their earliest demos, to be able to quickly share them with their friends in other parts of the country. Online access to the band’s early material would be instrumental in their growth, so much so that they would come to be known as the first band who used the internet and social media to build hype and achieve mainstream success. The funny thing is; the band didn’t do any of it.

In 2004, local Sheffield photographer Mark ‘The Sheriff’ Bull uploaded a collection of Arctic Monkeys demos to his own website, giving them the collective title Beneath the Boardwalk in honour of popular Sheffield venue, the Boardwalk, where Bull was handed a disc containing the songs. Fans could download the homemade album for free, and the songs quickly made their way to other file sharing sites. Around the same time, a fan-run Myspace was set up for the band, and the same collection of songs was added there too. It was a perfect storm; combining the hard-copy, grassroots efforts of the band’s distribution of demo CDs with the emergence of reliable internet connections and file sharing, meaning the Monkeys’ music was readily available at the fingertips of virtually anybody who sought to listen. By extension, the fact that this was driven by fans was another internet first; an early example of an online fan community that spent hours of their own time compiling and sharing things about their common interest – the Arctic Monkeys.

Arctic Monkeys themselves rejected the notion that their success was down to the internet. Guitarist Jamie Cook called it a ‘fluke and accident’, something that people jumped on without understanding what was going on around the band. Turner echoed Cook’s sentiment, saying it ‘right gets under our skin’ when they hear their success being put down to the internet. It’s true – the internet and social media may have helped spread word of mouth and allow people to learn the lyrics of unreleased songs inside out, but it always comes back to their material. This wouldn’t have happened if the songs were rubbish. This wouldn’t have happened to Razorlight. As Cook put it; ‘tunes were good’.

And yes, the tunes were good. Eight of the eighteen tracks on Beneath the Boardwalk made it on to Arctic Monkeys’ debut, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not. At 18 years old, the Monkeys’ had versions of now-iconic songs like ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’, ‘Mardy Bum’, ‘A Certain Romance’, and ‘Fake Tales of San Francisco’ already recorded and being passed around online. Aside from demo-level production quality, the songs were fully fledged, existing almost identically – lyrically and structurally – to the versions on the band’s first album.

Songs of this quality bouncing around forums and file sharing sites didn’t go under the radar for long. By March 2005, BBC Radio 1 had started to play the demo recording of ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’, and the band’s live performances had become stuff of legend. This was an unsigned act playing in venues holding – at most – a few hundred people, with every single person in the room screaming every word back at Alex Turner. By this point, the hype surrounding the band was nuclear; a peerless juggernaut destroying everything in its wake. Young people across the UK were going crazy for the Monkeys’ spikey, frantic, and raw take on post-punk; they weren’t singing about Alex Turner’s life – these songs were about their lives too.

In May 2005, Arctic Monkeys finally issued their first official release; Five Minutes with Arctic Monkeys, a two-song EP that contained ‘Fake Tales of San Francisco’ and ‘From the Ritz to the Rubble’. The release was limited to 1000 CDs and 500 7-inch vinyl records, and represented the first time that fans could hold an official, tangible release from the band. They were snapped up instantly – even by today’s standards – and now fetch thousands of pounds on eBay. So did this move signal a gear shift? Were Arctic Monkeys now in the business of shifting records? Of cashing in? Of selling out?

Nah. In a blatant act of Mark-Zuckerberg-uploading-his-first-app-for-free-instead-of-selling-to-Microsoft-because-he-knew-he’d-make-a-fortune-with-another-venture self-sabotage, the Arctic Monkeys intentionally excluded the barcode from the EP’s physical copies, making it ineligible for the singles charts. Those cheeky Monkeys.

In June, the band stuck to their guns and snubbed several major label deals, instead signing with independent label, Domino. The label – run by Laurence Bell – had recently experienced newfound levels of success by signing Franz Ferdinand, the Glasgow band who previously held the title as the UK’s indie kings. Arctic Monkeys had inherited their crown, and Domino was now home to both bands.

With the hysteria surrounding the band continuing to increase and the Domino record deal paving the way for the much-anticipated debut album, hype around the Arctic Monkeys’ live shows had reached fever pitch. A year before their sub-headliner slot on the main stage, the Arctic Monkeys played the Carling Tent at the 2005 Reading Festival, a stage usually reserved for unknown, unsigned acts. The tent was at capacity before the band were due on stage, prompting festival security to remove the walls of the tent to allow people to spill out around the perimeter and avoid a crush. By the time the band walked on stage, the crowd was eight-people deep beyond the back of the tent. That Carling Tent performance went down in history; one that every single person who went to Reading Festival in 2005 claims to have witnessed. As the NME put it, Reading organisers outdone their balls-up of booking 50 Cent in 2004 for a rock festival by ‘putting the most talked-about band in the universe on in a corner of the field in broad daylight’.

A hyped festival appearance is one thing – a cynic would say it’s easy to attract a big crowd in a mid-afternoon festival slot if you have some good tunes and aren’t up against anybody important. Arctic Monkeys’ gig at the 2000-capacity London Astoria was a completely different story. Indie kings versus iconic London venue. North versus South. Could this be the moment that the music industry finally catches up with the four lads from Sheffield? Would a half-full big boy venue stop the hype train in its tracks?

We’ll never know, because the Monkeys sold it out and touts were selling tickets for £100 (remember this was when gig tickets averaged at about £15). The entire gig is on YouTube and is something special, a time capsule of the era; from the band’s entrance soundtracked by Dr Dre’s ‘Xxplosive’ to the frantic race through a set of songs that would become their debut album, the footage shows the crowd eating out the palm of Turner’s hand.

You see the hysteria in full swing and get a sense of the electricity that would be in the room of an early Arctic Monkeys gig; the danger. Beer cans are flying from the balcony towards the band and the crowd in the floor standing section; Turner has to duck to dodge one travelling straight at his face during their opening song. The band’s instantly recognisable roadie, Big Nige, is constantly running back and forth on stage to mop up the spillages from the flying cans to avoid the band falling on a slippery stage. The issue of flying cans is finally addressed during the band’s third song – ‘Still Take You Home’ – when Turner warns the crowd ‘the next person that throws a fucking can…’ Not surprisingly, this threat has the opposite intended effect on the crowd’s behaviour.

The audience is constantly swelling like an ocean wave, left and right, back and forth, yet nobody pauses for breath, belting out every word. Bassist Andy Nicholson accidentally hits himself in the face with his bass guitar and needs to leave the stage to clean up a nosebleed, returning to chants of ‘you fat bastard’ from the crowd. Again Turner needs to intervene, telling the crowd to ‘shut the fuck up’ and that Nicholson will ‘fucking have you’.

Turner’s semi-playful, tongue-in-cheek disdain for the crowd is ever-present, as he addresses the hype around the band between songs: ‘so is this where all the celebs come and see us? London?’ and that ‘this time last year we hadn’t even played down London before, how’s about that for a stat?’ He even gives one fan something he’ll remember forever, pointing him out and declaring that he ‘looks just like Gareth from The Office – the fucking spit’. Lucky bastard.

Between the increasingly-hysterical UK gigs, between tours of major US cities and radio stations in an attempt to break America, the Monkeys lads kept their feet firmly on the ground. Matt Helders recalled reading a review of one of the band’s gigs in the NME whilst working at a call-centre; glancing at the magazine and seeing his picture whilst talking to a caller about their gas supply being shut off. Jamie Cook continued to work as a bathroom tiler between tours, throughout 2005 and even into 2006. Nobody could accuse the band of believing their own hype.

Speaking of believing the hype, there was one final move required before the band recorded and released their debut album. Their first official, label-released single. ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’, one of the earliest songs written by the band, was chosen. A ridiculously catchy two-and-a-half minute stormer of a track – with references to Romeo and Juliet and Duran Duran – that perfectly captured what the band were about; not that the release needed to be something that finally introduced the country to the band’s trademark sound anyway, as the demo version of the song was already receiving relentless radio airplay. The band chose to play the song live for the music video, shot in the vintage style of The Old Grey Whistle Test; a TV programme from the 70s that showcased bands like Talking Heads performing live. Turner has one warning for the viewer, delivered as if he is waiting for the moment that the band come crashing back down to earth: ‘don’t believe the hype’.

On Sunday 23rd October, Arctic Monkeys and their close friends had gathered in their local pub in High Green, Sheffield. Everyone eagerly sipped on their pints as they listened to BBC Radio 1’s singles chart countdown. All of a sudden, someone was dancing on the pool table. It was official – ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’ had went straight in at number one. Believe the hype.

For a band that seemed destined to deliver an iconic debut album so early into their careers, the process of recording Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not appeared to be pieced together quickly, without much preparation from Domino. Producer Jim Abbiss – who had most notably produced Kasabian’s self-titled debut album – registered an interest in producing the Monkeys’ album, like nearly every self-respecting producer in the UK, but was told by Laurence Bell at Domino that they wanted to go down a different path. Weeks later, whilst Abbiss was on holiday, he received a call to say that the Monkeys’ really needed to get something on tape, and he was asked if he would be able to come in and work on the album.

Tour and radio release commitments meant that the band only had 15 days available in which to record the album. In retrospect, the tight deadline to complete the entire album probably helped capture the raw energy that Arctic Monkeys were known for; a drawn-out process and months in the studio could have led to overthinking and overproducing the album. Luckily, Abbiss recognised the ingredient that made the band special, the thing that had drew people to the band; it was the sense of community, the personal connection that fans had with the songs and their lyrics. Abbiss had went to see Arctic Monkeys at The Grapes in preparation for working on the album, saying that ‘it wasn’t like a conventional gig – it was like a party. I just stood there thinking, if we can get anywhere near this kind of energy on tape then we’re on to a great record’.

Sonically, the album stays true to the live sound that Abbiss referenced. Spikey, frantic guitars; often favouring one-finger riffs that often incorporate dissonant, unconventional notes. Helders’ punchy, tight drums that combine with Nicholson’s bass to make club-worthy grooves, clearly drawing from the rhythms often found in the dub versions in the likes of Roots Manuva’s back catalogue. Turner snarls and spits through one hundred words a minute, delivering witty observations, hip-hop punchlines and sarcasm in his Sheffield drawl.

Abbiss and the Monkeys recorded the album in The Chapel, Lincolnshire, over an intensive two-week period. In preparation for the sessions, Alex Turner sent Abbiss an email containing the 13-song track list for the album. The list had five songs in italics and the other eight in standard text, with a note at the bottom: the five songs in italics tell a story, Alex’s view of a day and night in the life; the other eight songs were more general observations. Abbiss suggested that the band record the songs in the order they would appear on the album, meaning they went on the same journey during recording process.

Alex’s day and night in the life starts with ‘A View from the Afternoon’, where Turner is literally looking to the evening ahead from the safety of the afternoon. Although they claim it is unintentional, the opening line of the song (and album) doubles as a comment on a much-hyped night-out, as well as a much-hyped debut album: ‘anticipation has a habit to set you up for disappointment’. Can something that clever be a coincidence? So they claim. Modest Monkeys.

‘A View from the Afternoon’ starts with a bang – the entire band come flying out of the traps – before giving way to scratchy power chords, with Turner spitting out some of the common sights from a British night out; hen parties (‘the lairy girls hung out the window of the limousine’) and old-fashioned pub entertainment (‘I wanna see you take the jackpot out the fruit machine’). The band’s knack for connecting with the listener rears its head as Turner invites you to his table in his local pub, giving you some important advice; a warning that ‘you’ve got to understand that you can never beat The Bandit’, in reference to a notorious fruit machine from a Sheffield boozer.

The song’s chorus focuses on the age-old trope with a modern twist (for the mid-2000s); the struggle to say the right thing to someone you fancy, in the prehistoric world of chunky Nokia mobile phones. Turner has been here before – it happens every time; the drunk text spilling his guts out to the girl he likes, yet the only notable thing he is able to say to her is that she was drunk last night: ‘when she’s pressed the star after she’s pressed unlock/and there’s verse and chapter sat in her inbox/and all that it says is that you drank a lot’. With a sober afternoon head, Turner warns himself that he should ‘bear that in mind tonight’ and skip the drunk texting for a night, but he knows that the student nightclub drink promotions always win: ‘you can pour your heart out around three o’clock/when the two-for-ones have done the writer’s block’.

Turner’s night out continues with ‘Dancing Shoes’. Now in the club, he describes a scene of horny clubbers who all engage in the same act; the artifice of being there for the music and to dance with your mates, when in reality everybody is looking to pull. Despite the unspoken shared objective, no-one is forthcoming (‘but it’s oh so absurd, for you to say the first word so you’re waiting and waiting’), and the clubbers keep up the act, hinting towards their interest for someone but doing nothing about it (‘and some might exchange a glance/but keep pretending to dance’). The song’s chorus might feel like Turner is lamenting those around him, but he’s talking to himself. He does this every weekend, he knows everybody else is thinking the same thing – but they all get by with their half-hints in the hope that they hit the bullseye at some point during the three or four hours in the club, even though it could be achieved in five minutes if you plucked up the courage and just spoke to the person you liked: ‘the only reason that you came, so what you scared for/well don’t you always do the same, it’s what you’re there for but no’.

If ‘Dancing Shoes’ is Turner dwelling on the nightclub pulling process, ‘Still Take You Home’ is his realisation that time is ticking and he might need to lower his standards to pull a girl. In the wrong hands it could come across as crass, but these are 18-year-old lads; it’s how they would think. Turner has spotted a girl and convinces himself that she’s worth pursuing, despite his reservations (‘I don’t think you’re special, I don’t think you’re cool/you’re just probably alright, but under these lights you look beautiful’). She turns out to be an old acquaintance, and her makeover makes her think she can pretend that she doesn’t remember Alex: ‘well fancy seeing you in here, you’re all tarted up and you don’t look the same/I haven’t seen you since last year, yeah and surprisingly you have forgotten my name, but you know it’. Alex is fully accepting of his approach, repeating that despite her failure to impress him, he would still take her home. By the end of the song, Turner is a couple of drinks better off and has forgotten all of the things that put him off the girl (‘I fancy you with a passion’), then delivers a line that made it on to every mid-2000 female teenager’s Bebo profile; ‘you’re a Topshop princess, a rock star too’.

Every early 2010s indie kid Instagram profile had one; a dodgy, heavily-filtered picture of the small sign in a black hack taxi that warns passengers that the doors are locked, all because of Alex Turner. ‘Red Light Indicates Doors are Secured’ covers Alex’s view of the post-club scenery, narrated from the back of his taxi home. First he needs to secure that fabled taxi though, something we all know the challenges of. Time to get creative and chance your luck to squeeze six people in the taxi, otherwise they’ll need to find more than one lift: ‘ask if we can have six in, if not we’ll have to have two/well you’re coming up our end aren’t you? So I’ll get one with you’. Unfortunately the lads are up against a militant driver who rejects their extra person and their Styrofoam boxes filled with kebabs (‘won’t he let us have six in? especially not with the food/he could have just told us no though, he didn’t have to be rude’).

The conversation in the taxi bounces between the post-match analysis of their night out and commentary on the journey itself. Turner revisits one of the girls from the nightclub, who he actually managed to speak to (‘you see her with the green dress? She talked to me at the bar’), but his attention turns to more important matters when he clocks the price on the taxi meter (‘wait how come it’s already two pound fifty? We’ve only gone about a yard’). He recounts a scuffle in the taxi rank queue (‘these two lads squaring up, proper fighting’) and pities those involved (‘the kinda thing that’d seem so silly/but not when they’ve both had a few’). Reminiscing over the night out leads Turner to question why they decided to leave early (‘so why are we in a taxi, ‘cos I didn’t want to leave/I said it’s High Green, mate, via Hillsborough, please’), and the boys seek out one last act of mischief; jump out the taxi to bump the fare. ‘Went for it but the red light was showing/red light indicates doors are secured’.

Sunday morning arrives – the dust has settled – and Turner reminisces over last night’s antics in ‘From the Ritz to the Rubble’. The strict bouncers (‘his way or no way, totalitarian’) and the resulting nightclub knock back (‘so step out the queue, he makes examples of you’ and ‘you realise then that it’s finally the time/to walk back past ten thousand eyes in the line’). Despite considering another attempt to enter the same club (‘you can swap jumpers and make another move/instilled in your brain you’ve got something to prove/to all the smirking faces and the boys in black’), they reconsider, to Alex’s relief (‘well I’m so glad they turned us all away, we’ll put it down to fate’).

Alex compares the same town centre that was littered with drunk teens and taxi rank fights to the one he sees on Sunday morning (‘this town’s a different town today/this town’s a different town to what it was last night/you couldn’t have done that on a Sunday’), and spots a girl who was looking a lot better the night before (‘that girl’s a different girl to her you kissed last night/you couldn’t have done that on a Sunday’); maybe the girl from ‘Still Take You Home’, reconsidered without the pressure for the Saturday night pull. Turner makes it clear; all of the things that seemed so important on the Saturday night out suddenly feel insignificant now that the booze has worn off (‘last night, walked we talked about, it made so much sense/but now the haze has ascended, it don’t make no sense anymore’).

What a night.

The album’s title comes from a line from the 1960 film Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, a film centred on a young factory worker from the North of England who spends his weekends partying and having affairs with married women. Domino label boss Laurence Bell had given the band the DVD as a gift when they signed their record deal; a serendipitous twist for Bell to introduce the band to a film that has parallels with the story and subject matter of the album he was about to release, and it coming full circle when they name the album after a line from the film.

Five-song story arc aside, the album also focuses on Turner’s observations of the people around them as they attempt to make a success of the band. ‘Fake Tales of San Francisco’ holds a mirror to other local bands who live up to every cliché in the rock and roll handbook, having convinced themselves they hail from New York or California instead of the North of England. There’s the ‘super cool band’ with their trilbies, and the double entendre of the ‘weekend rockstars in the toilets, practicing their lines’. Turner isn’t the only one who isn’t impressed by the contrived antics of the other bands, as he recounts one girl’s feedback overheard at a gig (‘the band were fuckin’ wank, and I’m not having a nice time’).

The song’s chorus and outro is Turner’s direct response to the pretentious bands that the Arctic Monkeys encountered in their early days; he looks back to those early days and his open criticism of these people at their local gigs, where he dared the other bands and venue security to eject him (‘I don’t want to hear ya/kick me out, kick me out’). By the time we reach the song’s frenzied crescendo, Turner is speaking directly to all of the posers, practically climbing out of the speakers to scream his takedown in their face: ‘and yeah I’d love to tell you of my problem/you’re not from New York City, you’re from Rotherham/so get off the bandwagon/put down the handbook’. Arctic Monkeys have issued their visceral instruction; drop the pretentiousness and do your own thing, don’t copy what you see on TV or in the NME. Get off the bandwagon, put down the handbook. Get off the bandwagon, put down the handbook.

An even more direct bite back towards those closer to home comes in ‘Perhaps Vampires is a Bit Strong But…’ It’s one of the lesser known or discussed songs on the album but the lyrics are a pitch-perfect, sarcastic takedown of people who doubted Arctic Monkeys in their early days. People near Arctic Monkeys’ inner circle don’t think the band will amount to anything (‘I’ve seen your eyes as they fix on me/what is he doing? What on earth’s the plan? Has he got one?’), so Turner sarcastically demands that this local know-it-all helps them out (‘well you better give me some pointers/since you are the big rocket launcher, and I’m just the shotgun’). Turner reminds them that they aren’t in it to make a few quid; it’s their passion (‘well I ain’t got no dollar signs in my eyes/that might be a surprise but it’s true/I said I’m not like you’), and they couldn’t care less what they think (‘I don’t want your advice or your praise/or to move in the ways you do, and I never will’).

Pulling no punches, Turner labels these doubters as ‘vampires’, implying they suck the life and fun from everything. He recounts how people looked down their nose at the band for spending their weekends touring small venues in the North of England (‘I can’t believe that you drove all that way/well how much did they pay ya?’), once again sarcastically comparing this choice to what the vampires did every weekend (‘you’d have been better to stay round our way/thinking about things, but not actually doing the things’). Turner can see through their insincere support (‘though you pretend to stand by us/I know you’re certain we’ll fail’). Thank fuck they didn’t listen to the vampires.

Often mistakenly thought of as another song about a nightclub romance, ‘You Probably Couldn’t See for the Lights but You Were Staring Straight at Me’ is actually about Turner being flustered when he encountered the female singer from another up-and-coming band, The Little Flames. Arctic Monkeys and The Little Flames would often share the bill and tour together, and Alex took a liking to singer Eva Petersen. He spells out how she intimidated him (‘my heartbeat’s at its peak/when you’re coming up to speak’) and how he struggled to make a good impression (‘I’m talking gibberish/tip of the tongue but I can’t deliver it properly/and it’s all getting on top of me/and if it weren’t this dark you’d see how red my face has gone’).

But wait – plot twist. Who else was in The Little Flames, I hear you ask? No other than a plucky young guitarist from Liverpool; Miles Kane. Knowing what we know now (Milex/Last Shadow Puppets), we can only conclude that Alex was staring lovingly at Miles over Eva Petersen’s shoulder, and the song is actually about him. No point hiding from the truth.

To devote so few words to the next two songs feels blasphemous, but they are part of the psyche of every mid-2000 British teen; we know them inside and out. ‘Riot Van’ is a poignant change-of-pace, a story of working class kids being pulled up for underage drinking, and contains a peerless one-liner: ‘I’m sorry officer, is there a certain age you’re supposed to be? ‘cos nobody told me’.

‘Mardy Bum’ is about Turner’s experience of repeatedly falling out with a girlfriend, who he attempts to cheer up with ‘cuddles in the kitchen’. It begins with a twangy lead guitar line that lads and indie kids alike chanted at festivals and club nights across the country; a classic embrace-on-the-dancefloor number.

The 13th song on the album is ‘A Certain Romance’. The band were keen to capture the original essence of the song – written back in the Uncle Rodney’s days – without any rework or overdubbing. It was a case of agreeing when the time felt right and playing it through – once, ‘warts and all’. You hear Helders’ suggestion of ‘shall we keep rolling?’ at the beginning of the recording, before he launches into a pounding drum roll on his floor tom; an underrated pun for the drum roll/keep the tape rolling situation. That witty Monkey.

The song is inspired by a night in the band’s Uncle Rodney’s rehearsal space, where the band hosted an impromptu gig with a several other local bands, including ‘Reverend’ Jon McClure’s 1984. Each band brought their own group of mates to the Monkey’s rehearsal room; and only then did they realise that these different groups of people didn’t know each other. They weren’t all the same kind of people; some rough around the edges, some a bit more twee (‘oh they might wear classic Reeboks, or knackered Converse, or trackie bottoms tucked in socks’). In the classic, unavoidable routine that often happens when different crowds of teenage boys are thrown together (the playing field, the nightclub, the football terraces), tensions rose between the different groups (‘the points that there ain’t no romance around here’) and even the evening’s hosts felt threatened (‘they’d probably like to throw a punch at me’).

The song’s chorus represents the Monkey’s response to some of the attendees’ pleas to their hosts, asking them to try to keep the peace: ‘we’ll tell them if you like, we’ll tell them all tonight/they’ll never listen because their minds are made up/and of course it’s all OK, to carry on that way’. Turner knows their behaviour is unacceptable – but it’s tolerated. They’ll kiss and make up the next time they see each other. Boys will be boys.

What was probably always seen as a major perk to Uncle Rodney’s – the pool table – now looks like a bad idea, as people use the cues as accessories for their fight (‘don’t get me wrong, though, there’s boys in bands/and kids who like to scrap with pool cues in their hands’). During the song’s breakdown, Turner outlines the difficult position that he finds himself in, standing between his friends and the other aggressors in the middle of the riot: ‘well over there there’s friends of mine/what can I say I’ve known them for a long, long time/and they might overstep the line/but you just cannot get angry in the same way’. He’s not happy a fight has broken out, but as Tommy told Renton about Begbie in Trainspotting: he’s a mate, so what can you do?

The song kicks back into life as Turner’s guitar solo – simple yet effective – and Helders’ frantic drumming bring the album to a close. There’s something about those last driving notes from Turner’s solo and the pounding track behind it; it generates raw emotion inside of you. Maybe it’s the journey the album has taken you on, through the lives of Al and his band. Saturday night and Sunday morning.

The week prior to the album’s release, Domino released the band’s second official single: ‘When the Sun Goes Down’. To say it increased the already-hysterical anticipation for the album to a new level would probably be an understatement. The song instantly captured Britain’s imagination and lives forever in its lexicon. It’s easy to overlook the song’s genius out of pure fatigue of repetitive listens; you take it for granted these days, 15 years on, and you would be hard pushed to find someone who grew up in the era that can’t mimic the descending chords that follow the line, ‘she don’t do major credit cards, I doubt she does receipts/it’s all not quite legitimate’.

The song’s lyrics and music video showcase the Neepsend district of Sheffield, where the Monkeys’ rehearsal space – Uncle Rodney’s – was situated. It was a slightly-derelict, industrial area just outside the city centre (‘over the river going out of town’), and the song’s chorus is a repeat of the advice that the band had been given about hanging around outside their practice area late at night: watch out, lads; ‘it changes when the sun goes down around here’.

Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not was released on 23rd January, 2006. It went straight to number one and became the fastest selling debut album in British music history, selling over 360,000 copies in its first week on sale in the UK. It was a milestone moment in British music, but in British culture as well. The album’s appeal was and is universal, transcending the usual pigeonholes of indie or rock; it has become part of the fabric of British music – something that anything similar, musically or lyrically, will be held up against. Like in Liverpool after The Beatles, like in Seattle after Nirvana, and like in Manchester after Oasis, record label A&Rs descended on Sheffield to try and unearth the next Arctic Monkeys. Milburn – that band whose gig inspired the Monkeys to start a band – and Reverend and the Makers – fronted by Jon McClure, whose brother Chris appears on the front cover of the Monkeys’ debut album – were both given record deals after the success of Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not.

Turner’s lyrics were so clever and original that media outlets as prestigious as The Guardian ran stories that peddled potential conspiracy theories claiming that the band were manufactured and that songwriters must have been hired to contribute to the lyrics. The article cited Turner’s references to ‘Roxanne’ by The Police and ‘dancing to electro pop like a robot in 1984’, despite being born in 1986, as irrefutable evidence that these words couldn’t have come from young Al Turner.

The album connects with people in a special way; even people who don’t really like music will love some of the songs on this album. They hear the lyric, ‘just ‘cos he’s had a couple of cans, he thinks it’s alright to act like a dickhead’ and feel that it speaks to them. They do think it’s alright to act like a dickhead and they wear it like a badge of honour, even if Turner didn’t mean it as praise.

Turner's colloquial approach to his lyricism - his use of everyday, conversational English - is as engaging as his clever one liners. Describing a band as 'fucking wank’, or a prostitute working at night as ‘fucking freezing’, is not the kind of language you usually hear in music. You normally expect something more poetic, making Turner’s punchy, straight-forward delivery jarring and refreshing. This is how people speak. It’s not just about being a bit rough around the edges and adding ‘fucking’ before some words though; ‘there’s only music, so that there’s new ringtones’ is about as poignant as it gets, especially coming from the band who intentionally shunned the traditional path through the music industry.

So what happened next? Did they burn out, or surrender to the temptations of the rock-n-roll lifestyle? Not exactly. The band released their follow-up album – Favourite Worst Nightmare – a year later, another smash hit that kept the Monkeys locomotive steaming forward. The same year, they headlined the 2007 edition of Glastonbury, age 21, having never played there before. From that point on, their output has weaved across several genres and the band now has a chameleonic reputation for their ability to reinvent themselves, and never become stale. The approach works; their six studio albums all went straight in at number one on the UK album chart.

Not bad for some scruffy lads from Sheffield.